It was the 6th attempt in 1953 when K.M. Herrligkoffer, a German explorer, led another attempt titled “German-Austrian Willy Merkl Memorial Expedition to Nanga Parbat 1953”. In the past, 1930, 1932, 1934, 1937, 1938, 1939, the Germans made multiple unsuccessful and tragic attempts on the Nacked Mountain in Diamer, a remote Himalayan region in Gilgit-Baltistan. After WWII, finally in 1953, Hermann Buhl, one of the eight German-Austrian climbers, successfully reached the top of the killer mountain. On this occasion, the expedition was supported by the resilient Hunza Tigers, before the partition of former India, Sherpas used to be hired for climbing in the Karakoram-Himalayas. The former kingdom of Hunza and its people were well known in the West for their tough mountain lifestyle, as noted in the travel diaries of explorers in the late 18th century. The legendary stories about the Hunza might have influenced the Herrligkoffer to hire Hunzokutz, replacing the sherpas, as he admires in his book, Nanga Parbat 1953.

“Hunza climbers (Hunzahochträger) as a good replacement for the sherpas”.

As the famous climbers are coming from the Tyrol region, he even further claims;

“die Tiroler Typen in Gilgit sind alle Hunzas”; the Tyrolean types (looking) in Gilgit are all Hunzas (Herrligkoffer, 1953, pp. 50-51).Nanga Parbat became notorious for its inhospitality when an English mountaineer, AF Mummary, disappeared with two assistant climbers at the elevation of 6100m in 1895. It is known as the Killer Mountain, which claimed seven German mountaineers and nine Sherpa climbers in 1937. Consequently, Germans call it “Deutschen Schicksalsberg” (Germans’ Mountain of Destiny). Herrligkoffer lost his brother Willy Merkl during one of the German early expeditions in 1934. Not only is it Germany’s destined mountain, but the Sherpa community also sacrificed nine strong climbers.

Overlooked Local Heroes

The significant roles of indigenous climbers like Sherpas, Hunzokutz, and Baltis during Himalayan and Karakoram expeditions have often been overlooked by the mountaineering community. Unlike many Western climbers driven by national prestige, local mountaineers participated without aspirations for fame. The indigenous mountaineers, nevertheless, undertook significant risks to guarantee the success of these expeditions. The 1953 Nanga Parbat expedition, celebrated as a historic achievement, but the local crew’s contributions have largely gone unrecorded and unacknowledged. Ultimately, the local climbers are generically categorised, and their histories remain largely untold. This article aims to critically analyse the historical records, photographs, and written memoirs of the 1953 Nanga Parbat expedition, particularly Herrligkoffer’s book, Nanga Parbat 1953. Early expeditions to the Himalayas and Karakoram began during the colonial era, where the conquest of the unknown Greater Himalayan mountains became a race among colonial powers. A critical analysis of these historical records reveals a colonial mindset; for example, the hierarchical structure within expedition groups—dividing them into mountaineers, high-altitude porters, and porters—demonstrates a clear division between European climbers and local helpers. This raises questions about why initial expeditions motivated by national rivalry did not employ high-altitude porters from their own countries. Historical evidence shows that expedition supplies were fully equipped with luxuries such as gear, food, base camp infrastructure, and all necessary facilities transported from Europe. If transporting all these essentials was feasible, why did they not also hire high-altitude porters locally? It appears that labour exploitation in the colonies was considered a normal practice.Local Climbers, The Backbone of the Expedition

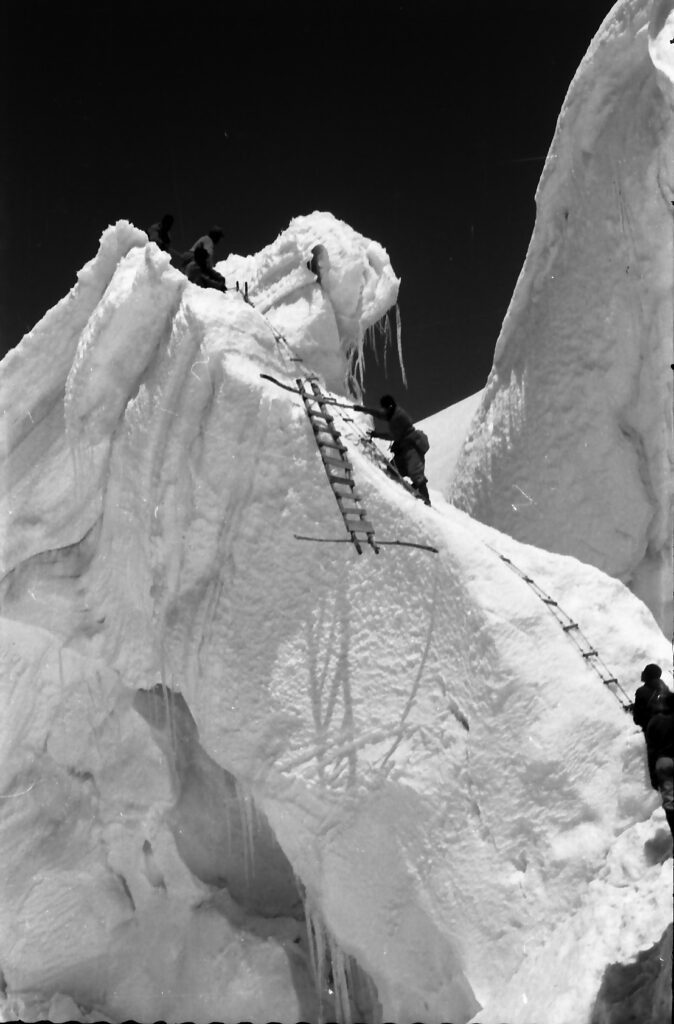

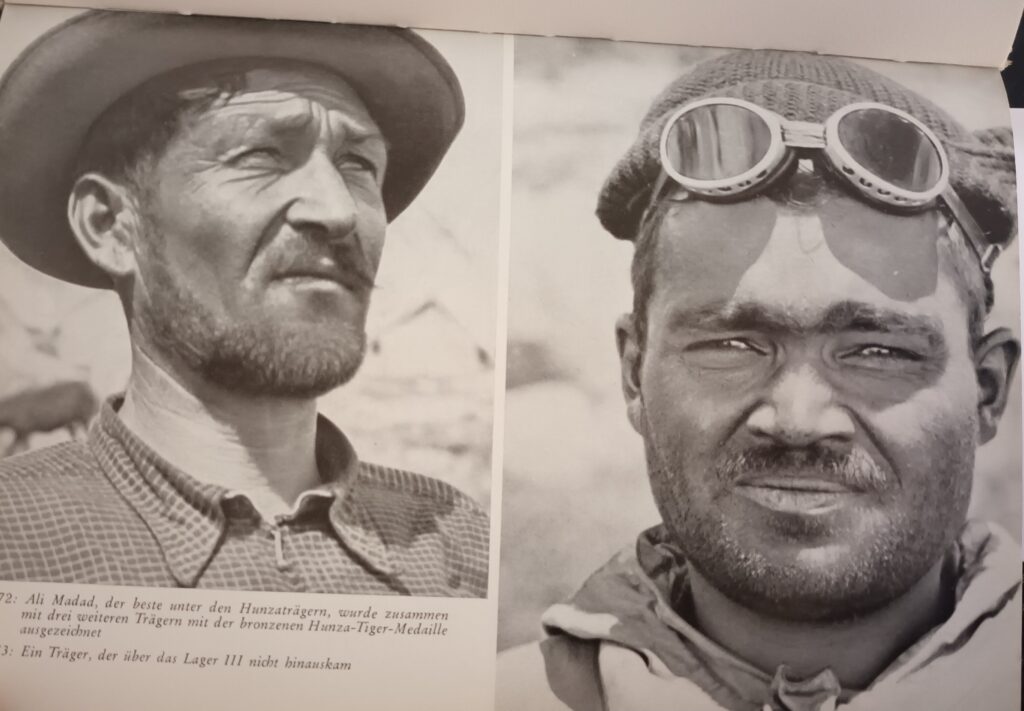

In his book Nanga Parbat 1953, Herrligkoffer himself acknowledges that previous expeditions failed due to insufficient numbers of porters (Herrligkoffer, 1953). Similarly, load carriers in Himalayan expeditions have been hired under harsh working conditions, neglecting labour ethics. From the examination of expedition reports, it seems that porters had protested several times against heavy loads, insufficient food supply and poor gear. On one occasion, reports state, porters did strike to reduce the load weight from 28 to 18kg. There were roughly 300 porters from Tato, Diamir and Hunza for carrying loads in the Nanga Parbat expedition in 1953. To support the high-altitude camps, strong men from Hunza were hired, who were later known as Hunza Tigers.“The terms of portering service were agreed that if the porters from Hunza turn back or run away from the expedition, they will be imprisoned by the kingdom of Hunza or sentenced to forced labour” (H.K NP 1953, P.88).

Furthermore, Herligkoffer claims that before leaving Hunza, the porters promised and took an oath to stand by German mountaineers (H.K. NP 1953, P.88).

The colonial outlook on Himalayan expeditions explains how local climbers remained underrated as high-altitude porters (Hochträgers). High-altitude porters are load carriers responsible for transporting supplies from the advanced camp to the summit. This colonial mindset undervalues the contribution of assisting climbers, effectively rendering them as forgotten climbers. In essence, they are not high-altitude climbers; instead, “assistant climbers”.Who were the Hunza Tigers

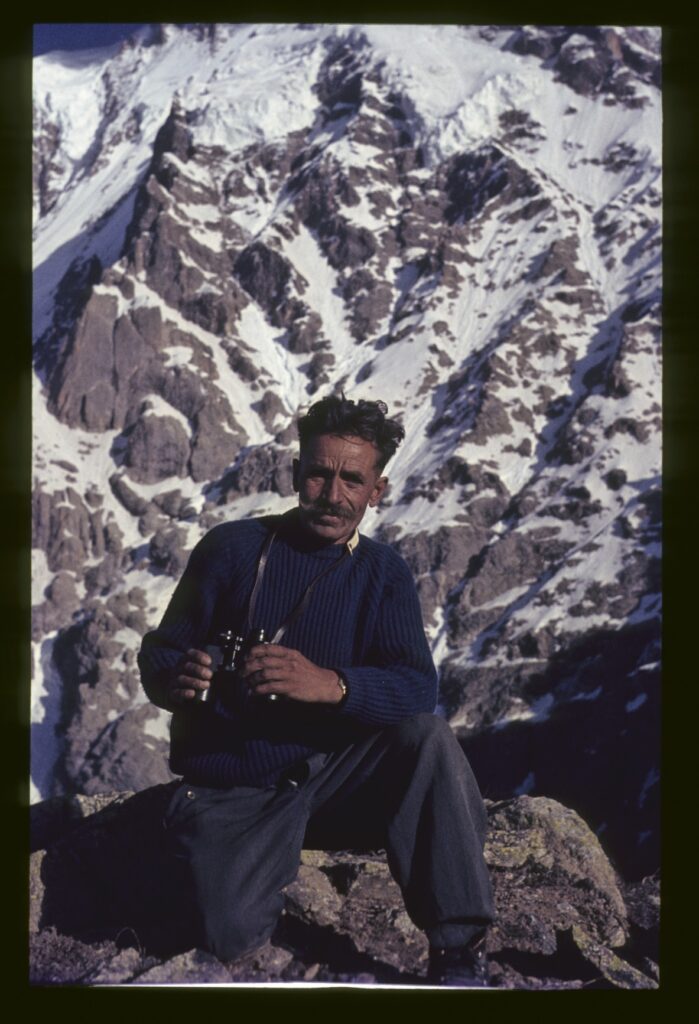

Such a historical injustice is the example of the Hunza Tigers, the overlooked local heroes of Nanga Parbat´s first ascent in 1953. Herrligkoffer himself acknowledges the unwavering support of local high-altitude porters, the Hunza Tigers (here onwards assisting climbers), in making the German-Austrian expedition to Nanga Parbat successful in 1953. For their great contributions in Nanga Parbat´s first ascent, the four local assistant climbers from Hunza valley received bronze medals titled Hunza Tigers, named Sardar Issa Khan, Amir Mehdi, Hidayat Khan, and Ali Madad.„Die Bezwingung des Nanga Parbat war mit den Hunzaträgern gerade noch möglich“ (Conquering Nanga Parbat was just about possible with the Hunza porters), (Herrligkoffer 1953 P.52).

Chosen by the Kingdom: How the Hunza Tigers Joined the Nanga Parbat Expedition

In an interview with Lambardar Aziz Ali, nephew of Sardar Issa Khan, he explained that the Hunza Tigers were not merely random high-altitude porters assembled at the last moment; they constituted a carefully selected group of brave men chosen by the Mir of Hunza, the former sovereign kingdom. In response to the 1953 German-Austrian Nanga Parbat expedition’s request for strong and loyal comrades, the Mir offered the most fit and resilient men from his kingdom, responded Izhar Chaboi, grandson of Amir Mehdi.These chosen elites from the kingdom, subsequently known as the Hunza Tigers. The careful selection back in the Hunza was instrumental to the success of the expedition, enduring harsh conditions and transporting substantial loads to higher camps. Their selection was not merely a matter of providing a strong labour force; it embodied a matter of honour, pride, and the kingdom´s representation on one of the most perilous peaks in the world.“Men who had been resilient through their experiences in hunting, building terrace fields, shepherding, and bravery in the Karakoram mountains were recruited to the expedition team”, said Aziz Ali during the interview.

Amir Mehdi (1913-1999) – the Hunza Tiger

Born in 1913 in Hunza, Amir Mehdi emerged as an extraordinary assistant climber, forever linked to the historic first ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1953. The following year, in 1954, he joined the ill-fated Italian expedition to K2. Battling fierce disputes and extreme conditions, he found himself having to bivouac in the open at a staggering elevation of 8000 meters, tragically losing his toes to frostbite and being betrayed, which cost him the chance to stand atop K2 first.

Sardar Issa Khan (1900-1986) – the Himalayan Tiger

Born in 1900 in Hunza, Sardar Issa Khan was a community leader called Lumbardar in his village, Baltit. According to his nephew, Aziz Ali, the “Sardar” title was given to him, which means the leader, since he was responsible for leading the Hunza´s expedition crew to Nanga Parbat. He was also leading the four high-altitude assistant climbers in the higher camps of Nanga Parbat, as Herrligkoffer frequently refers to Hunza Tigers as Issa Khan´s group. Issa Khan´s role in coordinating a big group of porters, leading them far away from the western Karakoram to Nanga Parbat, earned him the title of Sardar in the Karakoram mountaineering world.

Amazing work by Mr. Ajmal to comemoriate the contribution of our Ansestors from hunza in mounteering. These unsung heroes who introduced themselves to the hardest conditions with less resources back home in return made Hunza people proud .thank you Ajmal for this wounderful work hopes these heroes may be heard by world