The mountaineering community has overlooked the significant roles played by indigenous climbers, such as the Sherpas, Hunzokutz, and Baltis, during the Himalayan and Karakoram expeditions. Unlike many Western climbers who sought national prestige and global recognition in the race to be the first to summit, mountain communities in the Karakoram and Himalayas participated in early expeditions without aspirations for fame or material rewards. Often oblivious to the geopolitical and nationalistic rivalries that motivated European and American climbers in the early 20th century, these indigenous mountaineers risked their lives to ensure the success of such expeditions. The locals were motivated not by personal ambition but by a profound spiritual connection to the mountains they consider home. In contrast to their Western counterparts, local mountaineering communities maintained enduring traditions by performing rituals to honour and show respect for these sacred landscapes. Their approach to mountaineering was characterized not by conquest but by reverence, a perspective that remains distinct and invaluable in the history of Himalayan mountaineering.

Professor Ardito Desio’s 1954 Italian expedition to K2 is celebrated and hailed as a landmark accomplishment in the history of Karakorum mountaineering. This expedition was planned already in 1929 and was the first to successfully climb K2 in 1954, the second-highest peak in the world. Around 700 people made up the expedition’s enormous contingent, which included climbers, scientists, and more than 500 local porters (expedition crew) from Baltistan and the former kingdom of Hunza. There are hardly written records and data about the local crew members, such as personal profiles, biographies, photos and their climbing backgrounds. We find every detail about the climbers of classical Karakorum expeditions from their daily diary books, letters, photos, and documentaries. Still, unfortunately, the contributions of local climbers are not recorded formally. In the archives of mountaineering and climbing history, the local climbers are mentioned in very general terms as Balti porters, Hunzas, Sherpas, and so forth. For instance, the porters from Hunza are written in climbing records as Hunzas to this date, which is inappropriate; it should be either Hunzokutz or Hunzais.

Similarly, the local climbers who climbed up to the elevations of 7000 to 8000 meters with foreign climbers from early classical expeditions, e.g., Nanga Parbat 1953 and K2 1954, were given the name “high altitude porters”, but why are they not known as “assistant climbers”? Although the indigenous climbers had no experience in alpine climbing, they reached the 7000 to 8000 m elevations by climbing. Categorising a mountaineering expedition into so-called climbers, high-altitude porters, and porters overshadow the contributions of local “assistant climbers”. The role of “Hunza Tigers” – a title given to Hunzokutz assistant climbers on the Nanga Parbat expedition in 1953 – is an example of how the contributions of local climbers, particularly Amir Mehdi and Sardar Issa Khan, have been grossly overlooked, overshadowed by the feats of their international counterparts. Therefore, there is a need to unearth the climbing history to deconstruct and unveil the lacunas in the history of Karakorum-Himalayan climbing. There are some critical unanswered questions, therefore, which seek attention, and this discussion attempts to highlight the local perspective.

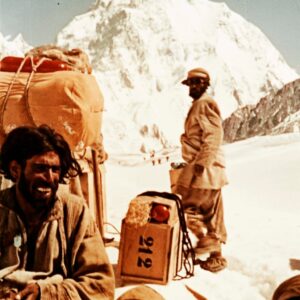

Source: Tirol Archiv Photographie TAP, Online Exhibition 2025

The Underappreciated Backbone of the Expedition

The harsh reality encountered by native porters and climbers is depicted in Professor Desio’s accounts, underscoring the immense disparities in recognition and treatment.

“May 9, on the left side of the Baltoro, it began to snow. The Baltis were not provided with winter outfits, nor could I provide them for such a large number of men.”

The local porters’ lack of appropriate gear and clothing highlights the mistreatment they endured. Despite these difficult circumstances, their resilience was essential to the expedition’s success.

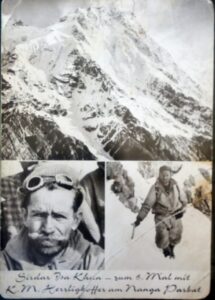

Source: Tirol Archiv Photographie TAP, Online Exhibition 2025

The Valor of Hunza Tigers, Amir Mehdi and Sardar Issa Khan

Amir Mehdi and Sardar Issa Khan, both hailing from Hunza, played pivotal roles in the success of the 1954 ascent. Their efforts, however, are barely acknowledged in Desio’s records, which predominantly focus on the Italian climbers. Desio’s statement, “At the same time the four men who were at camp 7 had set out with two oxygen respirators… In the course of the evening two Hunzas, Mahdi and Isakhan, also reached camp 7,” illustrates their significant involvement but fails to do justice to their contributions.

During the 1954 Italian K2 expedition, a serious injustice occurred involving Walter Bonatti and high-altitude porter Amir Mehdi, renowned as the “Hunza Tiger.” Bonatti was tasked with getting supplementary oxygen for the summit push, and he called on Mehdi to assist him because, as Mehdi’s son remembered,

“My father agreed to the mission because he was offered a chance to get to the top.” (BBC, 2014)

However, when they came back, they found that the designated camp (which was supposed to be at 7900–8000 m) had disappeared. Compagnoni and Lacedelli, rather than openly inviting Bonatti and Mehdi to the summit attempt, had secretly set up a camp at 8150 m to prevent their participation. The two had to survive a dangerous night without shelter, facing life-threatening circumstances. Mehdi, who had nurtured the dream for a long time of placing a Pakistani flag on top of K2—his son touchingly recalling,

“My father wanted to be the first Pakistani to put his country’s flag on top of K2, but in 1954, he was let down by the people he was trying to help.” (BBC, 2014)

He endured serious frostbite and injuries that deprived him of walking, which eventually led to the removal of his toes to avert infection. Even with his valorous sacrifice, Mehdi was let down by those in whom they had faith; this grim episode was mostly unwritten until many years later.

Amir Mehdi might not think of betraying a comrade on the high mountain, since it is the belief of mountain communities to avoid evil thoughts and acts on mountains. This mountain comradeship can be seen in the recent winter summit of Nepalis on the K2 in 2021. The communities growing up in the mountain valleys know how to protect a partner in need of help on the high mountains, which they believe is a moral responsibility. Muhammad Ali Sadpara´s unwavering support to his climbing partners on the winter expedition in 2021 demonstrates how the local climbers uphold the ethics of mountaineering.

It was a betrayal against Pakistan, and Pakistan missed the chance of K2’s first summit in 1954. There is a need for an appeal at the international level to investigate the crime against Mehdi on K2. Mehdi should be recognised as an equal partner in the first ascent of the K2. The government of Pakistan should raise this concern and appeal to international forums for justice—appeal for Amir Mehdi´s recognition. They misused his innocence and simplicity, making false promises of the summit. Ostensibly, it was a crime against Mehdi and disrespectful to the host country, Pakistan. Amir Mehdi and Sardar Issa Khan were instrumental in the arduous task of establishing higher camps, often risking their lives in the treacherous conditions of the death zone. Mehdi, in particular, suffered severe frostbite, a testament to his commitment and the extreme conditions.

Years later, as the complete story came to light—especially through Lacedelli’s book K2: The Price of Conquest—the controversy was brought before an Italian court. The legal dispute ultimately acknowledged the injustice committed against Amir Mehdi. His formal recognition came when the Italian government celebrated his heroic efforts and sacrifice on K2 by awarding him the rank of Cavaliere and the Italian civilian medal, Al Valor Civile.

Upon returning to his village Hassanabad Hunza, Mehdi never picked up his ice axe again. He spent the following decades wrenched by pain, financial difficulties, and the grief of betrayal. Mehdi died in 1999 at the age of 86, and it took until 2007 for the Italian Alpine Club to formally acknowledge his vital contributions to K2’s first ascent.

Discrimination and Exploitation of Local Climbers

An examination of Desio’s historical records on K2’s first expedition shows a pattern of discrimination and exploitation of local porters and climbers who were the backbone of the success of the first ascent. Local heroes like Amir Mehdi and Issa Khan, despite their major contributions, remain largely unacknowledged in the narratives of international mountaineering. The purpose of this discussion is to underscore their importance and call into question the Eurocentric depiction of mountaineering history, which frequently overlooks local contributions in favour of the glorification of Western climbers.

Source: Tirol Archiv Photographie TAP, Online Exhibition 2025

Desio demonstrates a distinct hierarchy between the local porters and the European mountaineers. He often designates the Italian climbers as “mountaineers,” while he labels the locals as “Baltis,” “Hunzas,” or even “coolies.” This linguistic difference manifests a colonial mentality that reduces the significance of indigenous climbers. In the words of Desio:

“On the 28th all the mountaineers and the Hunzas resumed their posts in the various camps on the Abruzzi spur and proceeded with the transport operations. But on July 1 the weather broke once more, the wind began to blow hard and the snow to fall.”

Desio and the broader expedition leadership diminished the contributions of locals to mere physical labour by failing to recognize them as climbers, even though they were hauling loads, navigating treacherous terrain, and enduring extreme conditions alongside the Italian team.

Source: Tirol Archiv Photographie TAP, Online Exhibition 2025

Интересная разбор, лично только что проверял по этой теме!

Your mode of explaining the whole thing in this piece of writing is actually good, all be capable of effortlessly be aware of

it, Thanks a lot. https://meds24.sbs/